Incunabula – a peek into the infancy of printing

For most people, viewing a book printed before 1501 would be possible only in a museum, from behind a sturdy glass case. I had the unique privilege of seeing it unpacked in a rare-book store before my very eyes! I was at the Whitmore Rare Books store in Pasadena (California), engrossed in a conversation with its owner Dan Whitmore, when his colleague walked in with a bag. It held a book wrapped in multiple protective layers.

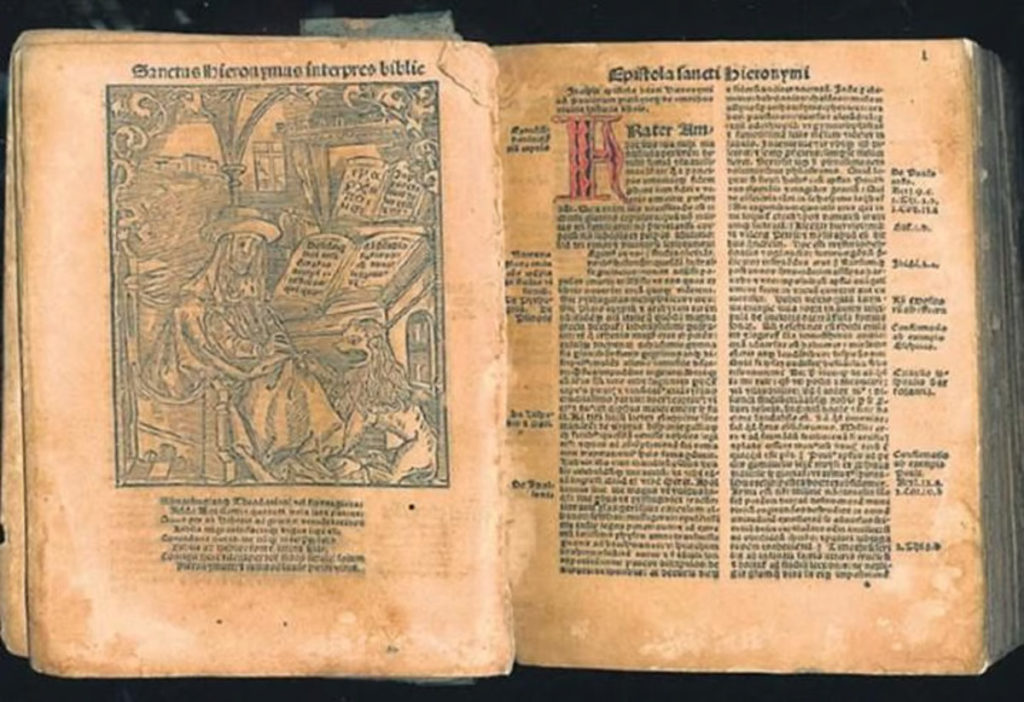

I could immediately sense the buzz around it because the director Miranda Nesler got up from her seat to observe the opening of the package. Only then I realised it was an incunabulum (or incunable, plural incunabula), the term for a book, pamphlet or other document that was printed, and not handwritten, in Europe before the year 1501.

The package contained William Caxton’s first full-length book Boke of the Fayt of Armes and of Chyualrye authored by the proto-feminist Christine de Pisan, printed in 1489. The book would cost — hold your breath — a whopping $450,000! I had been to the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, where I had seen some of the rarest private collections, and to the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, where two copies of the Gutenberg Bible were kept inside a bulletproof room, but the chance to see an incunabulum at such close quarters was priceless.

The first recorded usage of the term was in 1639 when the noted bibliophile Bernhard von Mallinckrodt issued a pamphlet to mark the bicentenary of the advent of printing by movable type titled De ortu et progressu artis typographicae (“Of the rise and progress of the typographic art”). In it, he used the phrase prima typographicae incunabula, “the first infancy of printing”, to describe books printed before 1501, a date chosen arbitrarily.

The Gutenberg Bible of 1455 and the Nuremberg Chronicle are incunabula that are examples of highly valuable literature. The Bavarian State Library is believed to have the largest collection of incunabula available. The most important contributions to the printing technology of incunabula came from Germany and Italy. Where only one or two manuscripts could be produced in a few months, several thousand copies of an edition could be made ready for publication – an astonishing technological breakthrough.

The earliest incunables were religious texts, mainly scripture. Soon, however, the Church in Europe realised how useful printed books could be for printing ecclesiastical documents, and they began commissioning printers. Once a printer had sufficient capital, the book could be adorned with decoration and colour. Government and political bodies such as the Court realised the potential of incunables as legal and social documents. The printed book firmly established itself as the primary source of instruction. As books became more common, their size and subject varied. There were devotional books of a smaller size that a household could use in its daily observation, and scholars could now afford books for their personal use.

Today, a rare incunabulum can bring over $500,000 at auction, and double that in a retail environment, and since very few individuals can afford them, most of them have been acquired by institutions. The Bibliographical Society of America published Incunabula in American Libraries to keep a census of all the fifteenth-century books recorded in North American collections. They add up to 50,000, which is one-third of the total in circulation worldwide.

Since incunables did not have title pages as we know them today, we most often find their printers’ names and publication dates on the final text page. This closing paragraph is called an “explicit” and typically names the author, printer, city of publication, and date of printing. As the interest in these earliest printed books increases and the number of publicly accessible incunables decreases, they will always remain the most sought-after books from a remarkable period in world history.